Chapter 2: Maize and how the Mother meets Modernity

In many ways, the story of maize is the story of what’s happened to our seeds. It’s the story of what’s happened to our culture. It’s the…

In many ways, the story of maize is the story of what’s happened to our seeds. It’s the story of what’s happened to our culture. It’s the story of a common field grass evolving into corn millenniums ago to become one of our most prevalent, storied, and revered foods in what we now call the Americas. And it’s then the story of the majority culture losing sight of this arc, the gifts and corresponding agreements with the Earth, and the people of the corn, turning this 10,000-year-old food into one of the most genetically modified crops grown at scale in our present-day.

Knowing some of this journey, I was hungry to bring a relationship with corn into my life and the land here. Hungry to find seeds beyond the reach of the billion-dollar enterprises wielding their power to erase what came before (and once sustained them) in the name of more money, now. Hungry to return to the unsevered wellness of my lineage before it met the story of modernity.

My journey begins on I-40, headed east, from the oldest mountains in the world to the coastal plains where my people come from. It’s early May, and my destination is Eastern North Carolina, a drive I’ve made many times, but this one feels different. My Mema is in the last chapter of her living days, and something tells me this quest for the seeds and what they hold is inextricably linked with her life, where we come from, and all she’s taught me. I feel like there’s one more lesson she has for me while she’s still alive, and I am to find it through the hands and words of our people with this longing for our ancient corn as my compass.

230 miles later, I’m three minutes away from the Lumbee Powwow, and I’m wondering what I’m doing here. A four-hour drive has become six as I unknowingly had maps set to “avoid highways” from a recent trip. I’m hungry and tired, and in this moment, I’m doubting that this call to the seeds will be answered. I see the sign for the Lumbee Cultural Center and I take a left, hearing the call of the drums. I drive up to the entry line, rolling down my passenger window to pay the entry fee. It’s a younger woman. She smiles and says, “Good to see you. Welcome.” I feel my shoulders melt. The knots in my belly unwind. I feel so at home with the way people talk here. The way they seem to take care of one another — and me a stranger to these parts, in my adult years.

I park, and as I step out of the car, the skies open. I’m soon soaked, but I don’t seem to care. I’m here. I can feel the drums in my chest. See the people. And my heart knows that this journey was not in vain. I fill up my water bottle, put down some tobacco, and head towards the powwow grounds.

The next two days are filled with stories, music, and some feeling in my bones that I do have a place here where the soil is still sand from what was once ocean. I meet a whole bunch of Locklears (recall that there are 14,000+ of them from Chapter 1, The Lumbee Sweet Potato) and a handful of Lumbees that know my Mema from her days living in Pembroke (my grandfather, a Lumbee teaching in Clinton, married his student, my grandma, a Coharie, and for good reason, they had to leave that school district for some time. They landed in Robeson County, the home of the Lumbee people, where my grandfather was originally from).

Late on the first evening, I’m wandering the outskirts of the powwow ground, trying to take it all in as I move underneath the pines. I cross paths with an elder man sitting in a replica of a traditional longhouse. He’s full of tales, and one of these is about a corn his family has grown for over one hundred years. He believes it to be a traditional corn of our people, and he gives me two bags with the hope I’ll help keep alive what’s dear to his family. Gleaning and grateful, I carry those two bags with me the rest of my time back east. By its color, I know it not to be our traditional corn, and still, I feel the answers to prayers starting to reveal themselves through the corn. I leave the swamplands feeling the cup of my grandfather’s lineage full and curious for what’s to emerge in the second half of my trip, back home in Coharie land in Clinton.

Maize comes from teosinte, a 2,000,000 year-old wild grass indigenous to modern-day Mexico. Early Indigenous peoples did not cultivate teosinte, but they would chew it like sugar cane to get the carbohydrates. The earliest forms of Chicha came from brewing the teosinte stalks. Around 10,000 years ago, something happens that becomes one of the biggest enablers of civilization’s growth in South, Central, and North America. The precursors to the Aztec, living in Oaxaca, Mexico, begin to select bigger ears of teosinte to become what we now call corn.

This is a moment referenced in creation stories across indigenous peoples. While these ancient cultures were much more adept in the realms of science than western history gives credence, this evolution of teosinte was equal parts in the realm of the mystery. Stories talk of this wild grass giving herself to domestication so the people could be fed. Corn was this vital part of the Mother, and here She was looking after Her children. There was an agreement made between the people and the corn, and a certain wildness and capacity for self-propagation was given to humans for something these peoples promised the corn. Some thing about taking care of the rest of life.

Prior to corn, nutrition was a lot harder to come by. It’s likely these Native peoples would have been eating what they could hunt, wild berries and fruits, and what we now think of as common weeds (lambs quarter, ragweed, amaranth). Very quickly, Maize became a dominant food source as it was 10–20x more productive than preceding plants and contained nutrients much more difficult to obtain in a wild diet. By 5000 BC, corn had made her way to Peru, and by 2000 BC, she’s in the modern-day United States. Once there, Maize only took 500 years to become a primary food source for most tribes. 4,000 years later, she still plays this role for Native peoples, despite so many efforts by the modern world to sever this relationship.

I had spoken to Greg Jacobs a handful of times in my adult years. He was serving for the second time as the Tribal Chairman for our Coharie people, and he understood this longing in me to touch, feel, and understand this rich lineage that I originate from within. Ahead of our meeting (for the first time since I was a young child), I had asked him about our corn. We weren’t actively growing any as a tribe, but he’d said he’d do some research to sort through the many gifts that he and the tribe had been given. There was a corn recently rematriated to our peoples from the academic world, but the story went that it didn’t germinate well, and the few extra seeds had been misplaced.

The time in Coharie land is full. Time on our river. Stories from our elders. My last few laughs with Mema. This continued whisper of a belonging to place and to land. On my second morning, Greg and I are visiting by the river as members of the tribe do video portraits for a piece being filmed by PBS. I’m telling him about this calling I feel from the seeds and how they seem to me a way to reconnect with the unsevered culture that came before us. A way to connect to the ways and stories that our people no longer consciously know.

He’s listening, intently, in this way I’ve come to know Greg for. As if he’s paying attention to what’s not being said as much as he is to what’s spoken. He raises a finger, and his deep voice beckons, “you know, Thomas, now that I think about it, there was this wild man from your neck of the woods. Incredible guy. Always barefoot. He’d hitchhike from Asheville to come see us. He gave Gordy [Greg’s brother and our Coharie chief] some corn a long time back, and I remember it being a Tuscarora Red.” A soft smiles comes upon my face; there is a possibility that our people still have some seeds.

The production team needs Greg, and he tells me he’ll call Gordy later that day to ask about the red corn. I head out kayaking on the creek for the afternoon, my first time being on this waterway that has fed our people for centuries and was recently restored by a collection of elders and youth, including Kullen, my guide for the day (and a friend from childhood when we’d spend summer vacations in Clinton). I feel settled on these waters. I feel an openness from the River Birch, the Pines, and the Oaks lining the banks. A feeling that I am familiar here. I see that this quest for seeds has led me to all the fullness that’s transpired in this time back east. In this, I realize the journey may not have been about the kernels themselves.

On my way back from the river, I swing by the tribal center to tell Greg goodbye before returning west. He never got a chance to call Gordy, and we talk about another trip soon back east. We hug, he wishes me well, and I head out the door to go give Mema one last kiss. As I climb in the car, I see Greg running towards me waving his hands. He’s on the phone with Gordy, and Gordy tells him he remembers seeing that red corn about a decade back in their father’s old shed. Greg looks up and says, “Who knows if it’s there, Thomas? That place is chaos, but it’s worth a shot if you’re interested.”

Any hinge of tiredness and dis-ease about the upcoming 4 hour drive through the night is overcome by this door cracking open. I swing open my passenger door, and Greg hops in. We have a few stops to make on our way across town, and I feel lucky to have any amount of time with this well of wisdom of a man, all made possible by these lost, but not forgotten red kernels.

Greg spends the drive to Indian Town Road telling me stories — of his youth here, his coming of age, and his trials. He tells me a story of the first time he was tribe leader; he was young and he had found himself amongst some questionable behavior. There was a forum to decide if he was fit for leadership. The tribe was not siding with Greg, and then a voice spoke up from the back. It was my Great Grandma Mary, Mema’s mom. As Greg tells it, people listened to her when she spoke, and she didn’t often. She said something like, “Now, I don’t condone what behavior Greg has been suspected of doing. But let me say this: which one of us has not faltered in our values and needed someone else to help us stand back on our feet? We’ve all been in Greg’s shoes before, and this is not the time to leave him alone.” As it goes, Great Grandma Mary sat back down, and that was the end of the meeting.

We arrive at Greg’s childhood home, and I’m hanging onto my last inhale in anticipation as we open the front door. I see Gordy’s shape, one of a worthiness that I’m coming to see in the Jacobs family. He sends me a big grin as he holds up an old salsa jar filled with glowing, red seeds. My expression quickly matches his. As is turns out, way back when Greg was leading the tribe for the first time, they were given these seeds. Gordy was a farmer all his life and so they were placed in his hands. But, it was at a time when he was moving away from tending land, as so many did, and they were never grown. Greg and Gordy think they’ve been in that jar for at least 30 years and inside reads a piece of paper, “Tuscarora Red, 200 years old.”

I knew it was highly unlikely these seeds would grow; most seeds lose germination within a few years if stored at room temperature. And still, I felt wealthy holding these seeds and whatever stories they carried. I left for home with that 1990’s salsa container in my cupholder, and it would be days before those would leave my sight.

For a 2,500 year stretch, corn was the foundation for much of what we now refer to as Indigenous America. Ceremonies and stories traveled north with the seeds from Mesoamerica and found their own place in the tribes of Turtle Island. New varieties were grown to adapt corn to each local environment, and seeds were traded across tribes to keep corn genetically diverse. The abundance of corn and its stability in storage enabled populations to grow and made increased space for leisure and beauty. The corn was remembered as this holy gift — one that continued asking something of the peoples who were fed by Her.

And then, before we could really realize what’s happening in a rapid acceleration of industrialization post World War II, corn meets modernity. In the 1970s, scientists, Stanley Cohen and Herbert Boyer, found a way to splice DNA at specific places in its sequence. This would begin a comprehensive journey into the genetic modification of most forms of life over the next 50 years. And the ownership by corporations over such modifications — one of the most poignant examples of the human delusion that our species is in control on this Earth.

In 1982, we meet the first approved genetically modified product, a human insulin. In 1994, the first plant, a tomato. In 2005, sugar beets (now one of the largest exports of this country and responsible for most sugar we consume). And in 2015, a genetically modified salmon. By 2017, just over 20 years after being introduced, 88% of corn grown in this country is genetically modified. Experts say now that no corn has been untouched by genetically modified genes due to genetic drift.

So, what’s the problem with genetic modification if it makes crops more “productive?” Some say seeds were never meant to be manipulated to then be owned by multi-national corporations. They’ve always been a part of the public domain, traded freely, honoring their sovereignty and revering the sustenance they provide. They’re a form of life — no more or less alive than human seed; who are we to play Scientific God? I personally find a lot of resonance here, and, there’s more, regardless of the myth of the world you find yourself situated within.

Intellectual property rights on a natural being were not made possible until the 1980s (corresponding to the development of genetic modification). By 2015, there were over 17,000 seeds patented in the United States by corporations. When a company receives a utility patent on a seed, they “own” that seed, dictating how it can be grown, who can grow it, and what agreements farmers must make to do so (for example, in most cases, saving seed for the next year’s crop is prohibited for farmers and sometimes biologically impossible with the modifications made). At present, 60% of the worldwide marketshare is in the hands of Bayer-Monsanta, DuPont, and Syngenta (this is in contrast to 1980 when the 10 largest seed companies only had only 15% of the market). Of course, seeds can never actually be owned any more than a piece of land or another human. But, through the lens of our social contract in the modern world, these companies have broad-sweeping rights in the legal system if their seed is ever found to be grown without being purchased (which happens quite frequently because of genetic drift where the GMO corn pollinates neighboring fields of open-pollinated corn).

Those three, multi-national corporations are also three of the largest six agricultural chemical producers. Their pesticides are made in conjunction with the genetically modified seeds with the seeds as the only form of life resistant to the chemicals in these applications and often dependent upon the specific chemical makeup of the fertilizers to even grow. In other words, to grow a vast majority of our most popular crops, a farmer has to use these patented pesticides and fertilizers alongside the patented seeds. This is at a time when already, modern agricultural practices have significantly decreased productivity on 23% of land, up to $577 billion of annual crop production is at risk of failure due to loss of pollinators from these very pesticides, and we’re on track to erode all topsoil in the next 50 years (making growing food in the ground wholly untenable).

In short, growing food is becoming increasingly dependent upon pesticides (contractually and biologically) that are decimating the natural systems that allow food to grow in the first place. The companies controlling the seeds are mandating these pesticides and fertilizers be used for their seeds to grow, and many farmers have no other choice but to grow these seeds. So, we’re in a downward spiral of destruction of our soils, our waterways, and our own bodies if we want to uphold the present food supply paradigm, of which we’re all participating.

In conjunction with the “ownership” of seeds by a handful of companies and pesticide producers, we’re seeing a massive consolidation of traditional varieties in the hands of a select few. There’s a global organizational based in France, The Consultative Group of International Agriculture Research (CGIAR). They presently store and manage over 750,000 seed accessions in 15 private seed banks (an accession is a plant variety collected at a specific time and location). Critics say that many of these seeds were taken without farmer’s consent across the global south, and in many cases, they were replaced with genetically modified seeds in the spirit of “better crop production.” Seeds that were kept for thousands of years across tens of thousands of sovereign “nations” or tribes are now in the hands of one organization from fifty years of work. Why is this necessary?

It is notable to me that CGIAR’s largest funder, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which has contributed more than $720 million since 2003, is also the largest private owner of farmland in the US. And The CropTrust, a sister organization to CGIAR who runs the famous “doomsday” seed vault in the Arctic: its funders include Bayer-Monsanto, DuPont,and Syngenta. You can make of this what you will, and at a minimum, it’s evident there is a momentous consolidation of ownership, control, and manipulation of these precious seeds and the land needed to grow our food.

The seeds have been the source of people’s power for thousands of years. It’s a good place to turn if you want a culture’s wellness, resource, and ultimately their sovereignty. Take it from the former US Sectary of Agriculture, Earl Butz, who said, “If food can be used as a weapon, we would be happy to use it.” Or from the “esteemed” George Washington, known as “town destroyer” by the Haudenosaunee people, who said to his general in a campaign to wipe out the Native people, “It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.” We’re playing out the same stories from 300 years ago, masked in a facade of benevolent aid. What’s left that hasn’t been rounded up, manipulated, and spit back out in the name of profit?

Holding this jar of red seeds, I knew there was some reason they hadn’t been thrown away. Seeds have a way of keeping stories alive — even if the seeds themselves aren’t viable to grow in the soil. I started researching Tuscarora Corn. The threads I’d gathered here and there presented a story that most of the tribes of modern-day North Carolina, including the Coharie and Lumbee, would have had roots back to the Tuscarora Confederacy, which some say was the largest nation spanning the Carolinas for hundreds of years. In the early 1700s, there was a massacre of the Tuscarora people (one of the largest, single massacres of Native peoples), and a majority of the handful of survivors fled north, eventually re-joining the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (also known as the Iroquois).

Accordingly, the few mentions I could find of a Tuscarora corn, the corn that would have been of my ancestors, were from seedkeepers in upstate New York and Ontario. I called the few numbers I could find and sent a Facebook message to a young man I’d heard of several times living close to the old Tuscarora reservation near the Virginia Coast who was taking care of some ancient seeds. These individuals were gracious in spending hours with me on the phone and via email, sharing what they knew.

As it turned out, that red corn that now sat prominently on my desk had the traits of a plains corn. It would not have been the traditional corn of the Tuscarora, but it had a story. In 1972, Native folks from all around the country descended on the Capitol as a part of the American Indian Movement. They were there to advocate for safer housing, better education, and more support from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The way I heard the story: they were peacefully protesting when a group of guards become violent with some women and children that were waiting in the front lobby. The tension escalated, and eventually, this group of 600+ Indians took over the Bureau of Indian Affairs for refuge from the onslaught of National Guard.

They ended up staying inside for six days while negotiations took place with President Nixon. During this time, they went through five stories of file cabinets, looking through artifacts, seeds, and historical records that the BIA had collected (often unwillingly) from tribes in the past century. In this collection of precious items, A Lumbee man by the name of Keever Locklear found his way to these red kernels. Once back to North Carolina, knowing the government would soon be at their doors to take back what the Native folks had re-claimed, Keever distributed this corn to over 100 families. If that many people were growing it, the government would never be able to find it all, he reasoned. So, those red kernels that I could not stop touching, they carried this story of resistance, rematriation, and the sowing of a revolution we’re watching germinate today.

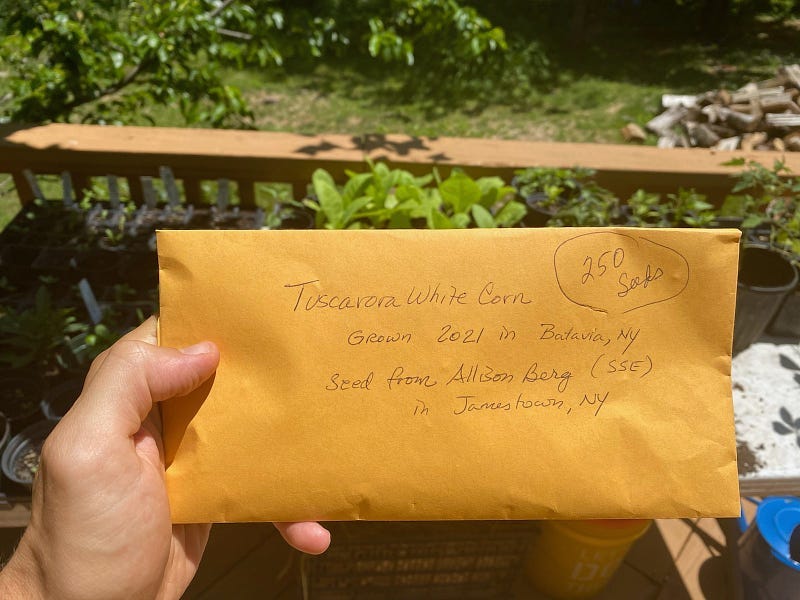

The Keever Red Corn had another gift for me. Through these conversations to identify its origin, I learned about our traditional corn, the Tuscarora White. It was a flour corn that came from South America into the highlands of Mexico just over 1,500 years ago. The corn likely made its way up through trade routes in the Southwestern United States to the Hopi peoples and eventually to the Tuscarora, who would have selected for this corn to thrive in the humid climate of the Carolinas. The few instances of these seeds still being grown I found online all pointed back to a Tuscarora Elder living on the northern reservation in the 1990s in upstate New York, Norton Rickard. As luck would have it, one NY seedkeeper was willing to share what he had left of his small stock.

He was selecting for stalks that put out 2+ cobs, and this meant he had a genetically un-diverse gene pool, at risk of in-breeding. He walked me through hours of all he knew of this corn and how he would approach caring for this corn over time. Through these exchanges and a few, old envelopes he located, a few more doors cracked open, and by late May, three different seedkeepers were sharing some of their Tuscarora White with our project here. This meant we’d be able to grow the corn this year without risk of inbreeding.

I eagerly awaited my evening walk to the mailboxes in the week these seeds were on their way. Holding these envelopes, I felt wealthier than holding a bag full of gold. These were seeds untouched by the grips of colonialism and domination. Here was Maize, still in her purest, life-offering form.

We decided to plant this corn in traditional mounds along with the Gete Okosumin Squash (a gift from Winona LaDuke and the Ojibwe Peoples) and the Cherokee Trail of Tears Beans. We made 4 rows of mounds: one with prayers for our own lives, one with prayers for our love and our family, one with prayers for this land and our community, and one with prayers for the planet. On a cancer-moon day in early June, we planted 4 kernels of Tuscarora White, one squash, and 8 beans in each mound.

There’s one more arc in the story of how we’re treating corn, and it’s the one that’s closest to home: our bodies. “The Seed Underground” has been my teacher here. Janisse Ray writes, “A study of 43 garden crops conducted by Dr. Donald Davis of the University of Texas-Austin found during the past 50 years, reliable declines in six nutrients: protein, calcium, phosphorus, iron, riboflavin, and Vitamin C. These drops ranged from 6 percent to as much as 38 percent.” Michael Pollen adds that we’ve seen a 30–40% decline in the nutritional value of our most common crops because we’re selecting for shelf stability, size, and color and not for the nutrition and vitality offered to our bodies.

And, there’s more to the picture. This modern orientation to our most fundamental, human need of sustenance could even be slowly killing us. Ray, “In rats fed GM [genetically modified] corn….scientists observed abnormal white and red blood cell counts, inflammation of the liver, and unexplained growths in stomachs and small intestines.” It makes sense — this isn’t food in any natural way of the word, and our animal bodies don’t know how to process it. Ray adds, “Some Iowa farmers reported infertility as much as 80% in hogs fed GM corn.”

The research isn’t “conclusive” on the impacts of genetically modified foods on humans (and why would it be when most large-scale studies are funded by the chemical companies), but it’s still something that worries the NIH. And while the verdict settles in court cases across the country, it’s our bodies bearing the impact. Over 92% of corn consumed in this country is genetically modified, and it’s estimated that 75% of processed foods have genetically modified ingredients. We’re destroying our soil, our waterways, and our own bodies as players in this game where someone else is setting the rules.

In contrast to this dystopia of factory farmed agriculture we find ourselves within, “Lab tests of ancestral beans collected from indigenous people, showed them to have eight to ten times as many antioxidants as grocery bought beans.” When we don’t have relationship with our food and we cannot see nor touch what’s happening, it enters a system where profit and production are the Gods we worship. It’s not our wellness as the center of any decision being made from the few setting the rules. And that has all kinds of immediate implications for Life — including ours.

This would be a fitting place to tell the story of how this Tuscarora White Corn has thrived in our soil, without genetic modification, pesticides, or artificial fertilizers. That would sure justify my righteous anger towards these systems that are destroying our planet in so many ways. But, it hasn’t, in the traditional sense. We planted the Cherokee beans before the corn had much of a head start, and much heavier than we anticipated as they climbed, they had taken down a quarter of the stalks when we returned from a trip to the Pacific Northwest. We lost another 25% of the corn over the course of two intense storms. These days hurt for me; I found myself angry, sad, and confused. I had visions of rows and rows of corn drying above the wood-stove, cornbread we’d be making all winter for our community, and seeds we’ve have to share with my tribe and the other tribes of North Carolina.

A corn genetically engineered to be stronger — to withstand wind — would have been much more productive for us. Fertilizers would have made for bigger, sturdier stalks. There is a reason we’ve systematically turned to these quick fixes when we live in a society running on a treadmill that’s only speeding up. Even growing another variety of corn from a neighbor that had been selected for these soils and climate would have been much more fruitful. We certainly would have had a lot more food for the winter, and I’d have less heartbreak in my life. And yet, none of these would have been the corn that my ancestors grew. The corn that shaped my genetic makeup and microbiome. None of these would have been the supple, golden-white kernels that grow on long, skinny cobs, that my bones have some remembrance of tending for centuries.

We won’t have an abundant harvest in the sense of quantity this year. If we’re lucky, we’ll have enough corn to save a genetically-diverse seed stock and for a few, special winter cornbreads. But in another sense, we’re wealthy in this corn because we’re now a part of Her story. For the rest of my life, Creator willing, I, my family, and my community will get to be in relationship with this corn. We’ll begin selecting for the kernels that grow into sturdy stalks — that can withstand heavy beans and big storms. We’ll begin selecting for the corn that makes the best cornbread and dries well in our climate. We’ll have the privilege of being in a lifetime of mutual exchange with this corn, being taken care of as we take care. I’ll get to tell my grandchildren the story of that first year we lost 75% of the corn that I’m passing down to them 50 years later. I’ll get to tell them we’re eating the same nutrients that sustained our ancestors for centuries.

Can genetic modification do some of these same things in the short-term? Maybe. But, I’m not willing to trade that convenience for the connection I feel calling from this corn. For this care I feel for her life and for her story. For how much sustenance and vitality she offers to my people and my future children because she grew up with us. I can imagine those few cornbreads we do get to have this year will fill us in a totally different way. I can imagine that this jar of seeds returned to my tribe will feel much more significant. There’s something I feel I’m earning by doing this with the Earth. The corn requires me to pay attention to a different arc, and when I heed that call, I find myself spending more time looking upon that which gives me my Life. Looking upon a much wider ecosystem. And noticing these currents. And being changed by them.

Here’s the thing: this corn, untouched by artificial tinkering and untreated with life-threatening chemicals, she still carries her thousands of years of knowing. Ten years from now, we will have naturally selected for stalks that can survive heavy beans and mountain storms. And, unlike genetically modified corn, which could do that in the short-term, this corn won’t have lost her story. She’ll carry all the traits that have been with her for millennia — many of which are hidden and unbeknownst to the human eye until they’re needed. Traits that know how to keep a people alive and keep them well on this Earth. When new life comes into our community, she’ll be ready to take special care. When those inevitable chapters of death and destruction come, she’ll know how to be with a people who are grieving. When a certain pest returns or the skies go dry for a few years, she’ll have a response. Not one that was engineered with human needles but one that was created with and by Nature, herself. One that honors that original agreement made between the Indigenous Peoples and Maize where Teosinte gave herself to take care of the human people.

I see this corn like I do an elder. There’s a reason we turn towards those who have lived the years of their life when we need our deepest reassurance. There’s a resilience than only time can impart. Unlike an elder, this corn isn’t on her way out of this physical plane; she’s vibrant and fluid, evolving noticeably year over year. A youthfulness that rests on top of thousands of years of roots that stretch down into the source of Life itself. For me, the story of genetic modification is the story of the shortcuts that seem to dominate our modern paradigm. We want things now, and we believe the illusion that their outer appearances represent the solidity of what lives inside. I choose food, home, and relationship that has bones. That has some remembrance of its place in the larger arc of life.

This Tuscarora White Corn knows how to survive. It comes from a lineage 10,000 years old that has seen hundreds of threats to its survival. At a time when we’re on the verge of collapse in so many ways, I choose the Ones that have earned their keep. I choose the Ones that ask me to slow down, to touch more of what gives me life, to situate myself between all those who came before and all those who are yet to come. That’s what the taking care of this corn means for me.

A “disclaimer:” I am not an expert on corn, and I’m certainly not the authority on Tuscarora White, the Tuscarora people, or Native cultures more broadly. I’m finding my way back to where I come from, which is a complicated and beautiful mess of lost stories, severed ties, colonization, resilience, and remembered connections. Some of what I share above I have been told. Some I have found online (and I’ve linked to this where-so). Some I’ve intuited as something in the outside world awakens something in my bones. Truth here is not absolute, and I’m not writing these posts to pretend to share truth in such a way. These words are intended to simply capture what I’m seeing through the lens of my lived experience. There are a myriad of ways to let in what’s being shared here, and I pray it will land in your heart in the exact ways it’s needing to.

A special thank you to: Stephen Smith, Daren Carrol, Fix Račhakwáhstha Cain, Yanna Fishman, Chris Smith, Zev Friedman, Steven Martyn, Janisse Ray, Elizabeth Hoover, Lori Belling, and Loren Muldowney for your seeds of inspiration and nurturing in this exploration and returning.

If you want to follow along on this journey as new stories emerge, there are a few options:

To the right of this story, you’ll see a photo of some corn with the title “SeedStory Tales.” If you have a medium account, click the email icon next to the “follow” button. From my understanding, you’ll get an email each time I share a new post.

You can follow along on Instagram here.